The Spectre

Whenever someone poses a challenge to fans of the superhero genre or DC Comics in particular, asking whether there are comics that do this or that, in recent years there was one answer that kept coming up:

Whenever someone poses a challenge to fans of the superhero genre or DC Comics in particular, asking whether there are comics that do this or that, in recent years there was one answer that kept coming up:

- Do any comics show devout Christians as sympathetic, intelligent people? Catholic priest Richard Craemer served as a valued friend and advisor for the Spectre.

- Are there any Jewish superheroes? Israeli hero Ramban appeared from time to time as an ally of the Spectre.

- Are there are any recent series to keep the same creative team for more than a couple years? Writer John Ostrander and artist Tom Mandrake did nearly every issue of The Spectre together for more than five years. Ostrander didn’t miss a single issue (64 of them, counting the #0 issue and an annual) even while dealing with his late wife Kim Yale’s cancer.

- Do any comics deal intelligently with real-world issues? The Spectre did on a regular basis.

- Which series has had the largest number of glow-in-the-dark covers in the shortest period of time? The Spectre had three in just the first 13 issues. (Issues #1 and #13 coincided with Hallowe’en.) The paperback collection of issues #1-4 also glows.

OK, so maybe the last one isn’t that great a claim to fame. But in general, The Spectre was a series that tried to do something different in the superhero genre. And it generally succeeded.

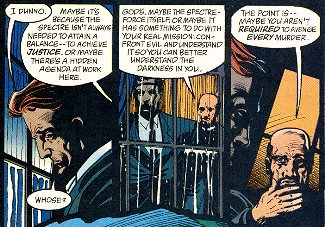

The character of the Spectre was a combination of two entities. (I use the past tense here because the series has ended, even though the character is arguably far from “over”.) One was Jim Corrigan, a hard-nosed guns-blazing cop, abused son of a fundamentalist preacher, killed by mobsters in the 1930’s. The other was the Wrath of God, the same spirit that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah and fulfilled Moses’ threat to plague Egypt. His somewhat nebulous calling was to confront evil… but to what end? To avenge murder, to fight demons, to understand the evil in his own soul, or what? Ostrander’s series was about Corrigan’s efforts to fulfill - and figure out - his mission.

The character of the Spectre was a combination of two entities. (I use the past tense here because the series has ended, even though the character is arguably far from “over”.) One was Jim Corrigan, a hard-nosed guns-blazing cop, abused son of a fundamentalist preacher, killed by mobsters in the 1930’s. The other was the Wrath of God, the same spirit that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah and fulfilled Moses’ threat to plague Egypt. His somewhat nebulous calling was to confront evil… but to what end? To avenge murder, to fight demons, to understand the evil in his own soul, or what? Ostrander’s series was about Corrigan’s efforts to fulfill - and figure out - his mission.

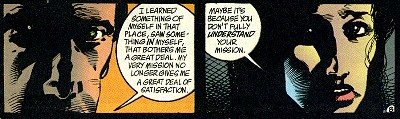

Corrigan was portrayed as a soul struggling… and with good reason. The kind of shoot-first-ask-questions-later cop that was considered a hero in 1940 isn’t regarded as all that noble by today’s standards. And Ostrander left that bit intact. Corrigan is not a particularly nice or charming person. And despite his rather personal contact with God - or perhaps because of it - he faced grave doubts about his worthiness, the justice of his mission, etc.

Corrigan was portrayed as a soul struggling… and with good reason. The kind of shoot-first-ask-questions-later cop that was considered a hero in 1940 isn’t regarded as all that noble by today’s standards. And Ostrander left that bit intact. Corrigan is not a particularly nice or charming person. And despite his rather personal contact with God - or perhaps because of it - he faced grave doubts about his worthiness, the justice of his mission, etc.

One mark of a comics writer’s quality is how well he deals with the “universe” his stories share with the works of others. For example, the Spectre was one of the oldest surviving characters in comics, created by Jerry Siegel and Bernard Bailey back in 1940 (in More Fun, one of the first comic book series). How well did Ostrander integrate his “take” on the Spectre with his previous incarnations?

I haven’t read very much of previous Spectre appearances, but it seems clear that Ostrander took pains to acknowledge his prior history, even incorporating it into his new stories. Unlike so many other heroes, the date of his origin remained fixed in the late 1930’s, which I like. Ostrander even did an issue featuring the Spectre’s Golden-Age sidekick (Percival Popp, Super Cop), a comic-relief character whom no one would have faulted Ostrander for sweeping under the rug in embarrassment. And more seriously, he included appearances by several classic Golden-Age characters, including the Spectre’s colleagues in the original 1940’s super-team, the Justice Society of America. Believably incorporating them into the serious metaphysical milieu of this series required focusing on some flaws and weaknesses in these characters (ones somewhat contrary to their simplistic portrayal 50 years ago), but it was generally done with respect for them. The Spectre #54, which deals with the late JSA member Mr. Terrific, is a good example of this. Likewise Ostrander’s inclusion of several of DC’s classic mystical characters (e.g. Madame Xanadu, Zatanna, Etrigan, Phantom Stranger, Dr. Fate).

I haven’t read very much of previous Spectre appearances, but it seems clear that Ostrander took pains to acknowledge his prior history, even incorporating it into his new stories. Unlike so many other heroes, the date of his origin remained fixed in the late 1930’s, which I like. Ostrander even did an issue featuring the Spectre’s Golden-Age sidekick (Percival Popp, Super Cop), a comic-relief character whom no one would have faulted Ostrander for sweeping under the rug in embarrassment. And more seriously, he included appearances by several classic Golden-Age characters, including the Spectre’s colleagues in the original 1940’s super-team, the Justice Society of America. Believably incorporating them into the serious metaphysical milieu of this series required focusing on some flaws and weaknesses in these characters (ones somewhat contrary to their simplistic portrayal 50 years ago), but it was generally done with respect for them. The Spectre #54, which deals with the late JSA member Mr. Terrific, is a good example of this. Likewise Ostrander’s inclusion of several of DC’s classic mystical characters (e.g. Madame Xanadu, Zatanna, Etrigan, Phantom Stranger, Dr. Fate).

Ostrander integrated his stories with the current DC Universe as well. Appearances by Superman and Batman (one each) made sense and told interesting stories. Because the Spectre was clearly the most powerful “hero” in the DCU, some accounting needed to be made of his role in major “events” like 1994’s “Zero Hour” (in which the universe was nearly wiped out), 1995’s “Underworld Unleashed” (in which a demon gave villains power in exchange for their souls), 1996’s “Final Night” (in which the sun went out), or 1997’s “Genesis” (in which the Source which powers the gods - and superheroes - was disrupted). While these kinds of “crossovers” often interest fans and boost sales, they tend to wreak havoc on individual ongoing storylines. Participation in these crossovers was voluntary, but Ostrander opted in, and succeeded in fitting these events into his stories almost seamlessly.

The month after Zero Hour finished, all of the DCU writers were required to do an “issue #0″, introducing some new (read: “different”) information about the hero’s origin. Ostrander had just (re)told his interpretation of the Spectre’s origin a year and a half before, but he managed to do just what the editors ordered, weaving the Spectre’s story in with Jewish, Christian, Hindu, and a few other religious traditions, explaining how it fits into the larger context of world history, and planting several seeds along the way for use in future stories.

One way to integrate well with everything else is to make your character and setting static. (That’s the time-honored strategy used with “big name” properties like Superman and Batman.) But that wasn’t Ostrander’s approach. Each major storyline presented a new challenge, threat, or question to Corrigan/Spectre, and each ended with the star (and often his supporting cast) in a different state… of mind, or even of soul. And there’s no question that the series didn’t end where it began. (A satisfying conclusion, I might add.)

One way to integrate well with everything else is to make your character and setting static. (That’s the time-honored strategy used with “big name” properties like Superman and Batman.) But that wasn’t Ostrander’s approach. Each major storyline presented a new challenge, threat, or question to Corrigan/Spectre, and each ended with the star (and often his supporting cast) in a different state… of mind, or even of soul. And there’s no question that the series didn’t end where it began. (A satisfying conclusion, I might add.)

In the process, Ostrander took on some thorny issues, ranging from the theological to the psychological to the sociological. He’s one of the few comics writers working today to consistently do stories with the kind of “social relevance” that Denny O’Neil experimented with in Green Lantern / Green Arrow 25 years ago. In the process he sometimes got a bit heavy-handed in his “message”. During the “Haunting of America” storyline, a letter-writer mistook Ostrander’s portrayal of discrimination against women in America for a satire of “extremist feminism”. (Though that particular misperception says as much about the letter-writer’s hang-ups as it does Ostrander’s, in my opinion.) The occasional thinly-veiled analogs of real-life people like O.J. Simpson, Kurt Cobain, and Rupert Murdoch came across as a bit blatant rather than insightful. I guess writing epic-scale stories about a character with the power to juggle planets tends to make one a wee bit bombastic.

One thing that helped keep the series down to earth was the supporting cast. It included Nate Kane, a (living) police detective who crossed paths with Corrigan early in the series and stayed on to, um, haunt him. The interplay between Corrigan and Kane was interesting because, contrary to cliché, they were not polar opposites. They were both tough cops with a strong sense of right and wrong and the will to enforce it. Their conflict came largely from their similarity to each other… and the dramatic difference that one was dead and had great supernatural power. And the fact that Kane kept saying “Balzac” whenever he was upset. Kane and Corrigan also shared an interest in the lovely Amy Beitermann, an early story element with lasting repercussions.

One thing that helped keep the series down to earth was the supporting cast. It included Nate Kane, a (living) police detective who crossed paths with Corrigan early in the series and stayed on to, um, haunt him. The interplay between Corrigan and Kane was interesting because, contrary to cliché, they were not polar opposites. They were both tough cops with a strong sense of right and wrong and the will to enforce it. Their conflict came largely from their similarity to each other… and the dramatic difference that one was dead and had great supernatural power. And the fact that Kane kept saying “Balzac” whenever he was upset. Kane and Corrigan also shared an interest in the lovely Amy Beitermann, an early story element with lasting repercussions.

Perhaps my favourite supporting character was Father Richard Craemer, a somewhat unorthodox Catholic priest. Craemer was a character Ostrander used in Suicide Squad, and it’s clear that he likes using him as a spiritual, well, father figure. He seems to be Ostrander’s idea of a “good Christian”: strong in his faith, courageous in his convictions, genuinely concerned about those in need of guidance, forgiving and understanding (even of his superiors and theological rivals), and a bit of a heretic. {grin}

Perhaps my favourite supporting character was Father Richard Craemer, a somewhat unorthodox Catholic priest. Craemer was a character Ostrander used in Suicide Squad, and it’s clear that he likes using him as a spiritual, well, father figure. He seems to be Ostrander’s idea of a “good Christian”: strong in his faith, courageous in his convictions, genuinely concerned about those in need of guidance, forgiving and understanding (even of his superiors and theological rivals), and a bit of a heretic. {grin}

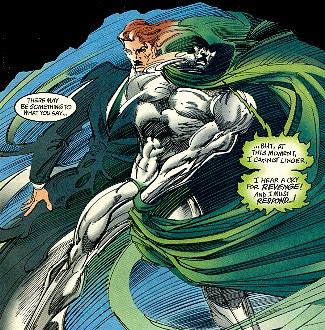

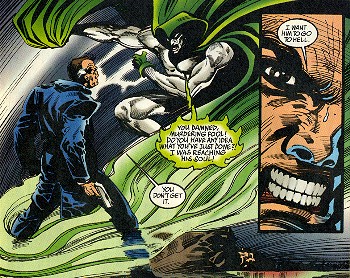

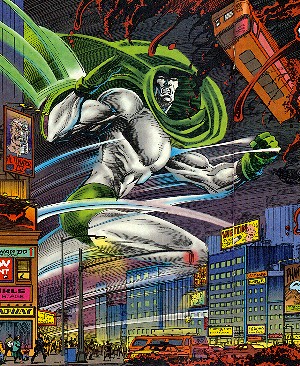

Mandrake’s art was definitely one of the things that made this series excel. Ostrander specifically wanted Mandrake for it, and I can’t think of a better artist for the series. The fact that he could both pencil and ink a full issue nearly every month (I count only nine monthly issues drawn by fill-in artists, over 5+ years) was made all the more impressive by the consistent quality of the work. The stories called for both mundane walking-down-the-street, talking-heads scenes of two ordinary humans, and larger-than-life surreal vistas of cosmic beings doing battle on other planes of existence. Mandrake did them all - especially the fantastic - with both care and imagination. The occasional fill-in artists (John Ridgway did a few issues) were all fairly good, but none of them matched the dynamic, expressive, detailed “look” that Mandrake brought to it.

Mandrake’s art was definitely one of the things that made this series excel. Ostrander specifically wanted Mandrake for it, and I can’t think of a better artist for the series. The fact that he could both pencil and ink a full issue nearly every month (I count only nine monthly issues drawn by fill-in artists, over 5+ years) was made all the more impressive by the consistent quality of the work. The stories called for both mundane walking-down-the-street, talking-heads scenes of two ordinary humans, and larger-than-life surreal vistas of cosmic beings doing battle on other planes of existence. Mandrake did them all - especially the fantastic - with both care and imagination. The occasional fill-in artists (John Ridgway did a few issues) were all fairly good, but none of them matched the dynamic, expressive, detailed “look” that Mandrake brought to it.

I should also give credit here to colorist Carla Feeny, color separators Digital Chameleon, and ace letterer Todd Klein - also members of the long-standing creative team, right up to the end - for their contributions. This series posed unique coloring and lettering challenges, which they rose to every month.

One thing Mandrake didn’t do is the covers (at least not usually). For the whole run of the series, editor Dan Raspler routinely commissioned covers (usually fully-painted) by a wide variety of artists. While they were usually well done, fascinating to look at, and distinctive from most other DCU books, they often had little or nothing to do with the contents; they were just pin-ups of the Spectre. There was usually some interesting stuff going on inside the books, and I wish they’d drawn attention to that, rather than just getting different artists’ interpretation of the “visual shticks” that some people assume comprised the full extent of the character.

Since I don’t expect anyone to go out and hunt down 64 issues (plus a few tie-ins from other series) just to see if they’d like the series, here’s a breakdown of the major storylines (the titles in quotes are ones given by the author; the others are mine), to give you an idea of what runs you might want to buy:

Since I don’t expect anyone to go out and hunt down 64 issues (plus a few tie-ins from other series) just to see if they’d like the series, here’s a breakdown of the major storylines (the titles in quotes are ones given by the author; the others are mine), to give you an idea of what runs you might want to buy:

- Intro of Amy Beitermann/Reaver, #1-12 (origin #3,4; #1-4 collected in Crimes and Punishments TPB)

- Judging the Earth, #13-18 - A watershed storyline that would inevitably have repercussions down the road.

- “The Spear of Destiny”, #19-22 - The repercussions. Appearances by the JSA (#20) and Superman (#22).

- History, #0,23-25 (Percival Popp, #24) - Starting with the creation of the Spectre force, this brings the past up to date, setting up a conflict with the Spectre’s arch enemy.

- Christmas, #26 - Yep, one of those sappy feel-good single-issue Christmas tales. It reads pretty well on its own and gives a good feel for the kinds of things the series deals with.

- “Desecration”, #27-31 - The Spectre is faced by Azmodus, an entity at his power level with a mad-on for him.

- “Year One”, annual #1 - The origin part is a good recap for readers not familiar with the character; the Dr.Fate team-up part is a good tale.

- “Monsters”, #32-34, Showcase ‘95 #8 - Some one-shots by other artists.

- “Underworld Unleashed”, #35,36, Underworld Unleashed: The Abyss - The Spectre should have just whupped Neron’s ass and prevented this whole event from happening. This was a reasonable excuse for why he didn’t.

- “The Haunting of America” #37-50, Superman: Man of Steel #54, (”Final Night”, #47) - A bit long and meandering with some distracting detours, but still effective.

- “A Savage Innocence” #51 - A one-shot of the Spectre vs. the Joker

- “The Haunting of Jim Corrigan” #52-56 - The Spectre investigates whether he is guilty of murder, and deserving of punishment.

- Also, #54 ties up an 18-year-old loose end that had been dangling since Justice League of America #172, about the murder of Mr. Terrific, introducing a successor to him.

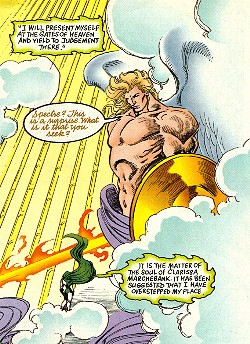

- “The Search for God” #57-62 - The Spectre finds the gates of Heaven ajar, and God missing… this is it, folks: the big finish, and the question to all your answers.

If you’re just curious whether you might like the series, try picking up the annual or #0 (October 94). Neither of them assumes previous familiarity with the series or characters, so they make good “jumping on points”. But if you’re really interested, the Crimes and Punishments TPB that starts at the very beginning is the very best place to start.