Seven Miles a Second

Most autobiographies lack one important element: an ending.

At the time they’re written, the author may be past the end of their career, and whatever events make their story “interesting” may be over, but their story isn’t yet over; they don’t yet know how it will end.

David Wojnarowicz, on the other hand, knew the ending to his story, having seen the Last Chapter of many other AIDS-affected lives. He also left behind his diary and writings, for his longtime friend and artistic collaborator to use in putting the ending in ink on paper, and adding the necessary images. And, according to Romberger, Wojnarowicz even sent him a message from beyond the grave to “finish the fucking

David Wojnarowicz, on the other hand, knew the ending to his story, having seen the Last Chapter of many other AIDS-affected lives. He also left behind his diary and writings, for his longtime friend and artistic collaborator to use in putting the ending in ink on paper, and adding the necessary images. And, according to Romberger, Wojnarowicz even sent him a message from beyond the grave to “finish the fucking

comic!” {smile}

Seven Miles A Second is one of the first two books from Vertigo’s new sub-imprint, Vérité (”truth”), which is supposed to deal more with real-world topics than Vertigo proper. Note, however, that this story actually is true. How often does any comics publisher (let alone DC) do non-fiction? That realism gives this slim volume a weight comparable to a magnum opus like Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby or Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta.

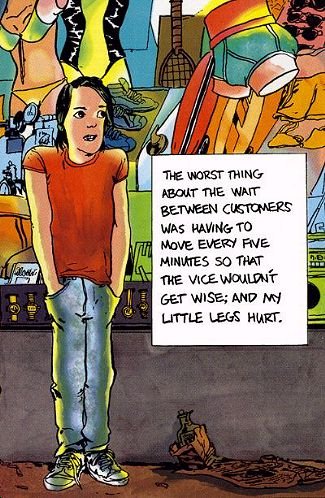

The book begins in Wojnarowicz’ childhood, a time of innocence… already long gone. It shows his life as a malnourished, homeless hustler, picking up middle-aged tricks on the streets of Manhattan. Wojnarowicz describes (and Romberger depicts) this life without sparing us the graphic details: of his hunger, thirst for security, and the depths to which he had to go for money. (If I had posted certain scanned excerpts from this chapter, enforcement of the U.S. Communications Decency Act would have probably made me eligible for prison. It’s not erotic, of course… just sexual.)

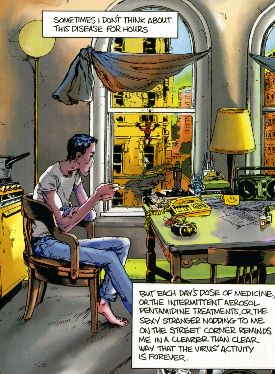

The final section deals with Wojnarowicz’ life as an adult, the daily struggle to feed and protect himself replaced with a daily struggle to maintain his failing health… and sanity.

The final section deals with Wojnarowicz’ life as an adult, the daily struggle to feed and protect himself replaced with a daily struggle to maintain his failing health… and sanity.

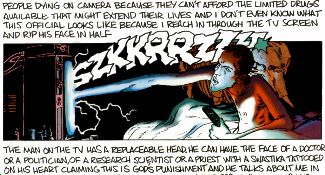

When you hear that Romberger finished the book after Wojnarowicz’ death, you might assume that the last several pages would lean on the art to tell the story, making up for the lack of a writer. But as the end approaches, Romberger lets his art take a back seat, using more and more text from Wojnarowicz’ diary to carry it. In this section, he’s as much an illustrator as “the artist”, providing surreal images to reflect the sometimes delirious and desperate experience Wojnarowicz describes.

Romberger’s art isn’t the sort I usually go for. It’s distorted, sketchy at times, and oddly colored (by punk artist Marguerite VanCook). But it fits this material quite well… after all, if the life of a hustler and person with AIDS isn’t a harsh distortion of How Things Ought To Be, I don’t know what is.

This is probably not a comic you’d want to give to your mother, and certainly not for the 12-year-old who elbows you out of the way to get at this week’s fanboy fodder. It’s not pretty, and often bitter and angry. But it’s compelling.

This is probably not a comic you’d want to give to your mother, and certainly not for the 12-year-old who elbows you out of the way to get at this week’s fanboy fodder. It’s not pretty, and often bitter and angry. But it’s compelling.

Et c’est la vérité.